Here's another way that life has changed in New Orleans since The Thing happened. Nobody but nobody trusts the US Mail with anything of any value or importance. During the storm some rain gutters came loose and crashed down onto the compressor/heat pump of our heating/AC system, seriously damaging it. We got it repaired last week and the repairman, who we knew well because he had installed the compressor some years before, politely but firmly refused to bill us and let us send him a check. Now, please. Likewise the treasurer for my Quarter condo association, when we were settling up back condo dues from when we were in Jackson, asked me please to just come by and drop off the check, no mailing.

With good reason, too. The postal service has always been rather odd here. (Everywhere else in the country post offices close at 5:00; here they close at 4:30. Go figure.) But even now after five months, mail service is completely unreliable, and everybody knows it. T-P columnist James Gill wrote about his wife applying for unemployment compensation. The claim was denied in a mailed notice, which said she could appeal if she filed within seven days. The notice arrived well after the seven day deadline. (Fortunately she was already back at work.) I'm waiting for a DVD from Netflix that is over a week overdue. That's just an annoyance, but other things are more serious. My health insurance company requires me to use their by-mail pharmacy for regular prescriptions. I ordered a refill of some allergy medication with plenty of time to spare, and indeed it has been shipped. But it has not arrived, and I'm out.

Worse still, all across the region people are struggling with financial disaster just from what the storm and floods did. Before long I fear we're going to start hearing stories of already desperate people finding themselves being hounded by collections agencies for failing to pay bills they never received. As if we need more trouble.

Sunday, January 29, 2006

Thursday, January 19, 2006

Now We Know

I'm a big fan of writer, columnist, and überblogger James Lileks, and I read his "Daily Bleat" just about every weekday. As an old radio man, he recently has been doing weekly podcasts, which he calls "Bleatcasts," usually featuring an eclectic selection of music and radio from previous eras. ("Eclectic" means he just wings it, but at least he's honest about it.) A tail end baby boomer, he has great and genuine affection for the popular culture of all eras of the 20th century, except for the 70s, affection he shows through ruthless mockery.

But in his Bleatcast for January 6, 2006, he presents us with something of great relevance to us here in New Orleans just now. It's from the 1998 movie of The X-Files, a scene in which David Duchovny's Agent Mulder is being briefed by Dr. Kurzweil, played by Martin Landau, who does the Terrified Insider Who Knows Too Much bit better than just about anybody. After all those seasons of Mulder and Scully digging for the Truth Beneath It All, Kurzweil is trying to finally fill Mulder in on what the real secret is, the real danger lurking in the dark, who's really behind it all, what we really should be afraid of:

[Note: All of Lileks's Bleatcasts are worth hearing in their entirety, but if you're really impatient you can right-click here, download it, and with the mp3 player of your choice fast-forward to the 14 minute point.]

But in his Bleatcast for January 6, 2006, he presents us with something of great relevance to us here in New Orleans just now. It's from the 1998 movie of The X-Files, a scene in which David Duchovny's Agent Mulder is being briefed by Dr. Kurzweil, played by Martin Landau, who does the Terrified Insider Who Knows Too Much bit better than just about anybody. After all those seasons of Mulder and Scully digging for the Truth Beneath It All, Kurzweil is trying to finally fill Mulder in on what the real secret is, the real danger lurking in the dark, who's really behind it all, what we really should be afraid of:

Kurtzweil: [frightened, breathy voice] Are you familiar with the hanta virus, agent Mulder?

Mulder: Yeah, it was a deadly virus spread by field mice in the Southwestern United States several years ago.

Kurtzweil: According to the newspaper FEMA was called out to manage an outbreak of the hanta virus. Are you familiar with what the Federal Emergency Management Agency's real power is? . . . FEMA allows the White House to suspend constitutional government upon declaration of a national emergency. Think about that!! What is an agency with such broad sweeping power doing managing a small viral outbreak in suburban Texas.?

[spooky music starts]

Kurtzweil: I think you know. . . . The timetable has been set. It'll happen on a holiday when people are away from their homes. The President will declare a state of emergency at which time all government, all federal agencies, will come under the power . . [whispers] . . of the Federal Emergency Management Agency. . . FEMA!! . . . . . The secret government . . .

Mulder: [pause]. . .They call me paranoid . . .

[Note: All of Lileks's Bleatcasts are worth hearing in their entirety, but if you're really impatient you can right-click here, download it, and with the mp3 player of your choice fast-forward to the 14 minute point.]

Monday, January 16, 2006

That City Council

Now that the mayor's Bring New Orleans Back commission has released its urban planning report, and now that the City Council has responded by screaming "Over our dead bodies!!", everyone's wondering, now just what the hell are they up to?

Protecting their own interests of course. When we first started talking about rebuilding, their position was that every neighborhood, no matter how badly flooded, should be immediately opened to rebuilding. This is not a plan, it is an absense of a plan, and would just be setting us up for a repeat of the disaster.

The BNOB plan at least has some realism to it. Some areas are going to be just too dangerous to repopulate, unless the Feds come up with Cat 5 levee protection. Much of the population has been scattered across the country, and the estimate is that by two years from now only half will have come back. Neighborhoods have to have a certain population density to be viable, and if dangerous neighborhoods end up lightly populated, it makes sense to buy out the property owners and help several neighborhoods consolidate into a new, properly dense neighborhood in a safer location.

That's the gist of it anyway. We're all still studying the details. We have to make sure it's flexible, for one thing. They estimate 200,000 will come back within a few years, but if 300,000 want to we can hardly tell them no.

But I was talking about the City Council. Why they were previously saying "rebuild everywhere!", and why they are now so furious about the idea of buyouts or, in the worst cases, confiscation through eminent domain. I can see several reasons for their behavior, some admirable, others less so.

One is that hard decisions are easier to accept if you make them yourself. When I was an AIDS Hotline counselor back in the 80s, the first thing they taught us in training was never to give advice. This struck me as odd, but they explained. People called because they needed help in making decisions with literally life or death consequences. But their best chance of sticking with a decision was if they made it themselves, not just followed advice. The most you could do was talk them through all the consequences of various choices, until they saw which ones made sense.

The Lower 9th Ward is never going to be restored to what it was. If they haven't already done so, many owners will come back, see what's left, and realize it is economically impossible to try and rebuild. For them, a buyout based on pre-Katrina property values is probably the best they will get. If the council is trying to get people to come back, make an assessment, and make those hard choices themselves, that's fine.

But.... Americans are not very good at meekly taking orders from authority. If it's hard enough to decide you can't rebuild, it's impossible to accept being TOLD you can't rebuild, and the very possibility of that produces the fury we've been seeing at public hearings. And as we humans have incredible powers of rationalization, anyone who is prevented from trying to recreate his destroyed home will believe to the day he dies that he could have put it all back together if the guv'mint had only given him a chance.

Property owners -- and voters -- who are in such an enraged state of mind are disinclined to re-elect. The council members know this, and know they will be the first to feel the voters' wrath if it comes to that. I fear that's why they are encouraging this fantasy that everything can be put back just the way it was if the mayor and the governor and so on would just give the go ahead. I think that they know perfectly well what is going to have to happen, that the physical and social architecture of the city is going to change. This is a more complex matter than just shrinking the boundaries, or "footprint", of the city. Much will change, and the City Council members are moving to make sure that the enraged displaced will see someone else as the bad guy, not them. That's fine up to a point, but when they go past that point they are trying to save their electoral skins at the risk of doing irreperable damage to New Orleans's chances of recovery. That's not fine at all.

Protecting their own interests of course. When we first started talking about rebuilding, their position was that every neighborhood, no matter how badly flooded, should be immediately opened to rebuilding. This is not a plan, it is an absense of a plan, and would just be setting us up for a repeat of the disaster.

The BNOB plan at least has some realism to it. Some areas are going to be just too dangerous to repopulate, unless the Feds come up with Cat 5 levee protection. Much of the population has been scattered across the country, and the estimate is that by two years from now only half will have come back. Neighborhoods have to have a certain population density to be viable, and if dangerous neighborhoods end up lightly populated, it makes sense to buy out the property owners and help several neighborhoods consolidate into a new, properly dense neighborhood in a safer location.

That's the gist of it anyway. We're all still studying the details. We have to make sure it's flexible, for one thing. They estimate 200,000 will come back within a few years, but if 300,000 want to we can hardly tell them no.

But I was talking about the City Council. Why they were previously saying "rebuild everywhere!", and why they are now so furious about the idea of buyouts or, in the worst cases, confiscation through eminent domain. I can see several reasons for their behavior, some admirable, others less so.

One is that hard decisions are easier to accept if you make them yourself. When I was an AIDS Hotline counselor back in the 80s, the first thing they taught us in training was never to give advice. This struck me as odd, but they explained. People called because they needed help in making decisions with literally life or death consequences. But their best chance of sticking with a decision was if they made it themselves, not just followed advice. The most you could do was talk them through all the consequences of various choices, until they saw which ones made sense.

The Lower 9th Ward is never going to be restored to what it was. If they haven't already done so, many owners will come back, see what's left, and realize it is economically impossible to try and rebuild. For them, a buyout based on pre-Katrina property values is probably the best they will get. If the council is trying to get people to come back, make an assessment, and make those hard choices themselves, that's fine.

But.... Americans are not very good at meekly taking orders from authority. If it's hard enough to decide you can't rebuild, it's impossible to accept being TOLD you can't rebuild, and the very possibility of that produces the fury we've been seeing at public hearings. And as we humans have incredible powers of rationalization, anyone who is prevented from trying to recreate his destroyed home will believe to the day he dies that he could have put it all back together if the guv'mint had only given him a chance.

Property owners -- and voters -- who are in such an enraged state of mind are disinclined to re-elect. The council members know this, and know they will be the first to feel the voters' wrath if it comes to that. I fear that's why they are encouraging this fantasy that everything can be put back just the way it was if the mayor and the governor and so on would just give the go ahead. I think that they know perfectly well what is going to have to happen, that the physical and social architecture of the city is going to change. This is a more complex matter than just shrinking the boundaries, or "footprint", of the city. Much will change, and the City Council members are moving to make sure that the enraged displaced will see someone else as the bad guy, not them. That's fine up to a point, but when they go past that point they are trying to save their electoral skins at the risk of doing irreperable damage to New Orleans's chances of recovery. That's not fine at all.

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

Next Stop Alpha Centauri

The highly regarded science weekly New Scientist has in its current issue, available online, an extraordinary article outlining the possibility of testing a form of warp drive within five years.

Allow me to repeat that: WARP DRIVE IN FIVE YEARS!!!!

It involves an extremely obscure branch of physics called Heim theory, worked out by an extremely obscure physicist, Burkhart Heim, in the 1950s. Heim was trying to reconcile the inconsistencies between quantum theory and Einstein's general relativity, a process postulating at least a few more dimensions than the ones we're familiar with, and along the way he came up with a way to, at least theoretically, propel a vessel many times faster than the ordinary speed of light.

Obviously this has never been tested. Very few people know about Heim theory, and hardly anyone understands it, as the mathematics are incredibly difficult. The person most able to promote Heim theory, Heim himself, shunned publicity due to the disfiguring injuries he suffered in an explosives accident towards the end of WWII. The only aspect of Heim theory that has been tested, in computer simulation at a lab in Germany, involves predicting the mass of elementary particles. In this, Heim theory succeeds wildly beyond the capabilities of conventional physics.

There is at least one advanced research facility that has said, if the math could be clarified for them and if they agreed it made sense, they might be able to physically test it within five years. Even if the test succeeds, of course, that's a long, long way from building the Enterprise-A. But to know it was even possible would completely revolutionize our view of the universe and our place in it. Think of it: Mars in three hours, a star 11 light years away in 80 days.

Boy I wish James Doohan had lived to hear of this. The thought that Scotty's beloved engine room might someday exist would have made his heart soar.

Allow me to repeat that: WARP DRIVE IN FIVE YEARS!!!!

It involves an extremely obscure branch of physics called Heim theory, worked out by an extremely obscure physicist, Burkhart Heim, in the 1950s. Heim was trying to reconcile the inconsistencies between quantum theory and Einstein's general relativity, a process postulating at least a few more dimensions than the ones we're familiar with, and along the way he came up with a way to, at least theoretically, propel a vessel many times faster than the ordinary speed of light.

Obviously this has never been tested. Very few people know about Heim theory, and hardly anyone understands it, as the mathematics are incredibly difficult. The person most able to promote Heim theory, Heim himself, shunned publicity due to the disfiguring injuries he suffered in an explosives accident towards the end of WWII. The only aspect of Heim theory that has been tested, in computer simulation at a lab in Germany, involves predicting the mass of elementary particles. In this, Heim theory succeeds wildly beyond the capabilities of conventional physics.

There is at least one advanced research facility that has said, if the math could be clarified for them and if they agreed it made sense, they might be able to physically test it within five years. Even if the test succeeds, of course, that's a long, long way from building the Enterprise-A. But to know it was even possible would completely revolutionize our view of the universe and our place in it. Think of it: Mars in three hours, a star 11 light years away in 80 days.

Boy I wish James Doohan had lived to hear of this. The thought that Scotty's beloved engine room might someday exist would have made his heart soar.

Monday, January 09, 2006

Cry Me a New Year

If you're a local reader you don't need to be told who Chris Rose is. If you're one of my legion of readers from elsewhere (Hi Mom!) he is a first rate columnist for the Times-Picayune, covering a general New Orleans cultural beat. We always knew he was good, but what he has written since Katrina has been phenomenal. He fled the storm with his wife and two small children, but within a week, once he had made them to safety, he was back, trying to convey the raw experience of what he saw and felt.

He is an incredibly honest reporter, whether or not it makes him look good. To round out 2005 he wrote an article, "Cry Me a New Year," and this passage breaks my heart every time I read it:

You can read that column here.

He is an incredibly honest reporter, whether or not it makes him look good. To round out 2005 he wrote an article, "Cry Me a New Year," and this passage breaks my heart every time I read it:

The first time I went to the Winn-Dixie after it reopened, I had all my purchases on the conveyer belt, plus a bottle of mouthwash. During the Days of Horror following the decimation of this city, I had gone into the foul and darkened store and lifted a bottle.

I was operating under the "take only what you need" clause that the strays who remained behind in this godforsaken place invoked in the early days.

My thinking was that it was in everyone's best interest if I had a bottle of mouthwash.

When the cashier rang up my groceries all those weeks later, I tried, as subtly as possible, to hand her the bottle and ask her if she could see that it was put back on the shelf. She was confused by my action and offered to void the purchase if I didn't want the bottle.

I told her it's not that I didn't want it, but that I wished to pay for it and could she please see that it was put back on the shelf. More confusion ensued and the line behind me got longer and it felt very hot and crowded all of a sudden and I tried to tell her: "Look, when the store was closed . . . you know . . . after the thing . . . I took . . ."

The words wouldn't come. Only the tears.

The people in line behind me stood stoic and patient, public meltdowns being as common as discarded kitchen appliances in this town.

What's that over there? Oh, it's just some dude crying his butt off. Nothing new here. Show's over people, move along.

The cashier, an older woman, finally grasped my pathetic gesture, my lowly attempt to make amends, my fulfillment to a promise I made to myself to repay anyone I had stolen from.

"I get it, baby," she said, and she gently took the bottle from my hands and I gathered my groceries and walked sobbing from the store.

She was kind to me. I probably will never see her again, but I will never forget her. That bottle. That store. All the fury that prevailed. The fear.

You can read that column here.

Sunday, January 08, 2006

Fun with FEMA

Tim has some fascinating insights into what it's like dealing with FEMA in New Orleans these days, though of course, he's not complaining.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Back to the Misery Tour

In December Time magazine ran their annual feature of the best photos of the previous year. Not surprisingly, Katrina photos led the pack. One of the most dramatic was this photo by the acclaimed photojournalist Thomas Dworzak:

It captures vividly the unreality and sheer craziness of the situation in New Orleans at that time, just after the storm had passed and the levees had broken; buildings surrounded by water yet engulfed in flame. [Note: click on any of these pictures for a closer look.] Time made only one mistake. In the photo caption they located this scene in the Garden District, an area closer to Downtown where many of the most beautiful old 19th century mansions can be found. It isn't. It's Uptown in the 2100 block of Napoleon Avenue, about ten blocks from my house. This is what that center building looks like today:

The grass in the foreground is where all that water was. It's a small park with a playground. I sometimes walk my dog there. That palm tree can be seen in Dworzak's photo, silhouetted against the right edge of the right-hand fireball. The houses producing that fireball were fairly expensive condos. This is what's left:

In the center of this photo is a sort of rust-covered metal frame. That is the skeletal remains of an upright piano.

If there's any good news, it's this. I've learned to read these sort of markings well enough to know that the "0" on the bottom means no bodies were found here. The people who lived here may have lost all their possessions, but not their lives.

What's depressing is the realization that, since I drive past here fairly often, I'm going to have to look at these ruined shells for months, if not years. There's too much work to be done on houses that can still be salvaged to spare any effort to clean up a total loss like this.

It captures vividly the unreality and sheer craziness of the situation in New Orleans at that time, just after the storm had passed and the levees had broken; buildings surrounded by water yet engulfed in flame. [Note: click on any of these pictures for a closer look.] Time made only one mistake. In the photo caption they located this scene in the Garden District, an area closer to Downtown where many of the most beautiful old 19th century mansions can be found. It isn't. It's Uptown in the 2100 block of Napoleon Avenue, about ten blocks from my house. This is what that center building looks like today:

The grass in the foreground is where all that water was. It's a small park with a playground. I sometimes walk my dog there. That palm tree can be seen in Dworzak's photo, silhouetted against the right edge of the right-hand fireball. The houses producing that fireball were fairly expensive condos. This is what's left:

In the center of this photo is a sort of rust-covered metal frame. That is the skeletal remains of an upright piano.

If there's any good news, it's this. I've learned to read these sort of markings well enough to know that the "0" on the bottom means no bodies were found here. The people who lived here may have lost all their possessions, but not their lives.

What's depressing is the realization that, since I drive past here fairly often, I'm going to have to look at these ruined shells for months, if not years. There's too much work to be done on houses that can still be salvaged to spare any effort to clean up a total loss like this.

Wednesday, January 04, 2006

Story Time

I seem to be drifting towards stating my views on the contentious subject of multiculturalism. If so, then before I do I'm going to take the chance to tell an absolutely wonderful story, a cautionary tale about not underestimating people. It comes from a book by Robert Georges called People Studying People that I read as a textbook when I was in grad school.

During the 1890s university academics, particularly in the US, started rethinking the question of how to study and research non-Western societies, especially the less developed ones. The previous attitude had been to dismiss as "primitive" any societies that did not have an extensive written history, and even some that did, such as Japan, China and India, tended to be patronized just for not being European.

Scholars came to realize that there was much of interest and value in such cultures, but realized it was going to be difficult to get at by the means they were used to. Societies without libraries and archives are impenetrable to a scholar if libraries and archives are all he knows. So over this period they developed the practice of what we now call fieldwork, studying a society by immersing yourself in it. Living among the people you're studying, learning their language, their songs and legends, helping to hunt or farm. Learning their way of life by sharing it for a while. This seems obvious to us now, but it was revolutionary then.

Among the first cultures to be studied this way were American Indian tribes, and for good reason. They were easy to get to by train and horseback, there was always somebody around who spoke English, and since scholars were still trying to feel their way, develop these techniques, it was a lot safer to study the Navaho than to plunge into the jungles of New Guinea.

Around 1905 a young man from a university back east arrived on a reservation to do his fieldwork. As I cannot remember his name (Amazon will sell you Georges's book if you're dying to know), I will just call him the Scholar. He had made arrangements to live with a local family, and had been there a week or two, just finding his way around, when he was approached by a young man with the wondrous and unforgettable name of Wolf Lies Down. He wanted to know what the Scholar was doing there. He wasn't hostile or anything, but wondered if the Scholar was maybe a trader looking to buy some of the tribe's horses, and maybe they could do some business.

The Scholar wanted to answer honestly, but wasn't quite sure how. How to explain such abstract notions as scholarship and research to this local lad? But he had heard that when explaining difficult concepts to children, one started with the most concrete examples and worked your way up to the abstract. What would work with children would surely work with this simple aborigine.

So he said, "Well, I want to talk to you, to your friends and family, and find out how you live. I want to see the houses you live in and the clothes you wear. I want to see the food your grow, and watch how your women cook it. I want to see the games your children play, and hear the songs they sing. I want to listen to the stories your old men tell, stories of how the world came to be and how it was when they were young. I want to...."

And he was working up some enthusiasm here, really getting on a roll when Wolf Lies Down, who had never in his life been off the reservation, interrupted him and said, "Ah! I see. You're an ethnologist," smiled politely, nodded, and walked away.

It is to my everlasting sorrow that the Scholar did not record his own reaction to this incident.

During the 1890s university academics, particularly in the US, started rethinking the question of how to study and research non-Western societies, especially the less developed ones. The previous attitude had been to dismiss as "primitive" any societies that did not have an extensive written history, and even some that did, such as Japan, China and India, tended to be patronized just for not being European.

Scholars came to realize that there was much of interest and value in such cultures, but realized it was going to be difficult to get at by the means they were used to. Societies without libraries and archives are impenetrable to a scholar if libraries and archives are all he knows. So over this period they developed the practice of what we now call fieldwork, studying a society by immersing yourself in it. Living among the people you're studying, learning their language, their songs and legends, helping to hunt or farm. Learning their way of life by sharing it for a while. This seems obvious to us now, but it was revolutionary then.

Among the first cultures to be studied this way were American Indian tribes, and for good reason. They were easy to get to by train and horseback, there was always somebody around who spoke English, and since scholars were still trying to feel their way, develop these techniques, it was a lot safer to study the Navaho than to plunge into the jungles of New Guinea.

Around 1905 a young man from a university back east arrived on a reservation to do his fieldwork. As I cannot remember his name (Amazon will sell you Georges's book if you're dying to know), I will just call him the Scholar. He had made arrangements to live with a local family, and had been there a week or two, just finding his way around, when he was approached by a young man with the wondrous and unforgettable name of Wolf Lies Down. He wanted to know what the Scholar was doing there. He wasn't hostile or anything, but wondered if the Scholar was maybe a trader looking to buy some of the tribe's horses, and maybe they could do some business.

The Scholar wanted to answer honestly, but wasn't quite sure how. How to explain such abstract notions as scholarship and research to this local lad? But he had heard that when explaining difficult concepts to children, one started with the most concrete examples and worked your way up to the abstract. What would work with children would surely work with this simple aborigine.

So he said, "Well, I want to talk to you, to your friends and family, and find out how you live. I want to see the houses you live in and the clothes you wear. I want to see the food your grow, and watch how your women cook it. I want to see the games your children play, and hear the songs they sing. I want to listen to the stories your old men tell, stories of how the world came to be and how it was when they were young. I want to...."

And he was working up some enthusiasm here, really getting on a roll when Wolf Lies Down, who had never in his life been off the reservation, interrupted him and said, "Ah! I see. You're an ethnologist," smiled politely, nodded, and walked away.

It is to my everlasting sorrow that the Scholar did not record his own reaction to this incident.

Monday, January 02, 2006

Not Schadenfreude

I really take no pleasure at all at the plight of the folks in Northern California just now. Hell, that's where I come from, and nobody could be more sensitive to the tragedy of flood damage than the people who live where I do now. But when I saw this picture on the front page of the New York Times . . .

. . . can I be forgiven a slight feeling of something like relief at seeing a water related disaster photo that was not taken in Louisiana?

. . . can I be forgiven a slight feeling of something like relief at seeing a water related disaster photo that was not taken in Louisiana?

Sunday, January 01, 2006

Go Cosmopolitans!

Occasionally one is lucky enough to run across a book or article that neatly crystallizes your feelings and thoughts on a subject, brings into focus what you've long since believed and helps you conceptualize the reasons for what you've thought all along. This article from today's New York Times magazine does it brilliantly for me on the subjects of multiculturalism, cultural imperialism, preserving traditional ways of life, and so on. The verdict: more cultural contamination, please.

The author, Kwame Anthony Appiah, should know. He's a native of Ghana and related by marriage to the most recent three Ashante kings. But his mother is British and he teaches philosphy at Princeton University. He makes a strong argument for the position that the cultural preservationists, such as those in Unesco who recently passed a resolution for the "protection and promotion" of cultural diversity, are not only fighting a losing battle, they have taken a side which should lose.

Preserving cultural artifacts, like artwork or music or architecture or history, is fine. But those who would preserve entire traditional cultures because they're somehow more "authentic" than the modern world make a terrible mistake. They forget that a charmingly authentic African village is usually that way because its people are too poor to be otherwise. They may be desperate to change, to modernize, knowing full well what modernization will bring, but don't have the resources. You cannot preserve the culture of a poor rural area -- as opposed to its cultural artifacts -- without locking its people into poverty, with all the disease, misery, short life expectancy, and infant mortality that poverty produces. This is hardly an act of kindness, and certainly not what they would choose for themselves.

Not only is this a cruel thing to do, not only is it impossible -- there is no village in Ghana so poor it doesn't have radios, and most Ghanaians have cell phones -- but it's ridiculous and foolish, as there simply are no pure and authentic cultures anywhere. Haven't been for thousands of years. We've been mixing and matching ever since we became human.

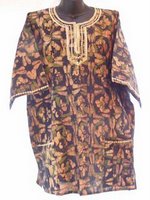

Here's a lovely example I gleaned from the article. If you say "traditional African" to most Americans, they think first off in terms of clothing. Every year at Kwanzaa you'll see African-Americans wearing something like this:

An ancient African clothmaking tradition, right? Hardly. That kind of cloth is called a Java print, as its origins are in the Javanese batik print cloth imported into Africa in the 19th century by Dutch traders. Sometimes the cloth didn't even come from Java, but was made and printed by the Dutch themselves. Think about that. 19th century cloth mill owners in Holland making printed cloth they thought Africans would like and would buy, thereby both reflecting and influencing the "traditional" look of African clothing.

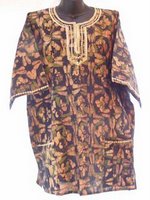

You want something more traditional, you might go for some authentic kente cloth, like this:

This is handwoven cloth, a traditional handcraft of the highest quality, and the finest and most expensive kente cloth is made in the village of Bonwire out of silk. Wait a minute, silk? Are silkworms native to Africa? Indeed they are not. They're native to Asia, and the silk for kente cloth has always been imported, again usually by Europeans.

So you can't preserve pure, authentic, traditional cultures, because there aren't any. Anywhere.

There's more in the article. It's worth a read.

The author, Kwame Anthony Appiah, should know. He's a native of Ghana and related by marriage to the most recent three Ashante kings. But his mother is British and he teaches philosphy at Princeton University. He makes a strong argument for the position that the cultural preservationists, such as those in Unesco who recently passed a resolution for the "protection and promotion" of cultural diversity, are not only fighting a losing battle, they have taken a side which should lose.

Preserving cultural artifacts, like artwork or music or architecture or history, is fine. But those who would preserve entire traditional cultures because they're somehow more "authentic" than the modern world make a terrible mistake. They forget that a charmingly authentic African village is usually that way because its people are too poor to be otherwise. They may be desperate to change, to modernize, knowing full well what modernization will bring, but don't have the resources. You cannot preserve the culture of a poor rural area -- as opposed to its cultural artifacts -- without locking its people into poverty, with all the disease, misery, short life expectancy, and infant mortality that poverty produces. This is hardly an act of kindness, and certainly not what they would choose for themselves.

Not only is this a cruel thing to do, not only is it impossible -- there is no village in Ghana so poor it doesn't have radios, and most Ghanaians have cell phones -- but it's ridiculous and foolish, as there simply are no pure and authentic cultures anywhere. Haven't been for thousands of years. We've been mixing and matching ever since we became human.

Here's a lovely example I gleaned from the article. If you say "traditional African" to most Americans, they think first off in terms of clothing. Every year at Kwanzaa you'll see African-Americans wearing something like this:

An ancient African clothmaking tradition, right? Hardly. That kind of cloth is called a Java print, as its origins are in the Javanese batik print cloth imported into Africa in the 19th century by Dutch traders. Sometimes the cloth didn't even come from Java, but was made and printed by the Dutch themselves. Think about that. 19th century cloth mill owners in Holland making printed cloth they thought Africans would like and would buy, thereby both reflecting and influencing the "traditional" look of African clothing.

You want something more traditional, you might go for some authentic kente cloth, like this:

This is handwoven cloth, a traditional handcraft of the highest quality, and the finest and most expensive kente cloth is made in the village of Bonwire out of silk. Wait a minute, silk? Are silkworms native to Africa? Indeed they are not. They're native to Asia, and the silk for kente cloth has always been imported, again usually by Europeans.

So you can't preserve pure, authentic, traditional cultures, because there aren't any. Anywhere.

There's more in the article. It's worth a read.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)